A Day In The Life of a Viper Innovations Field Service Engineer

June 1, 2023

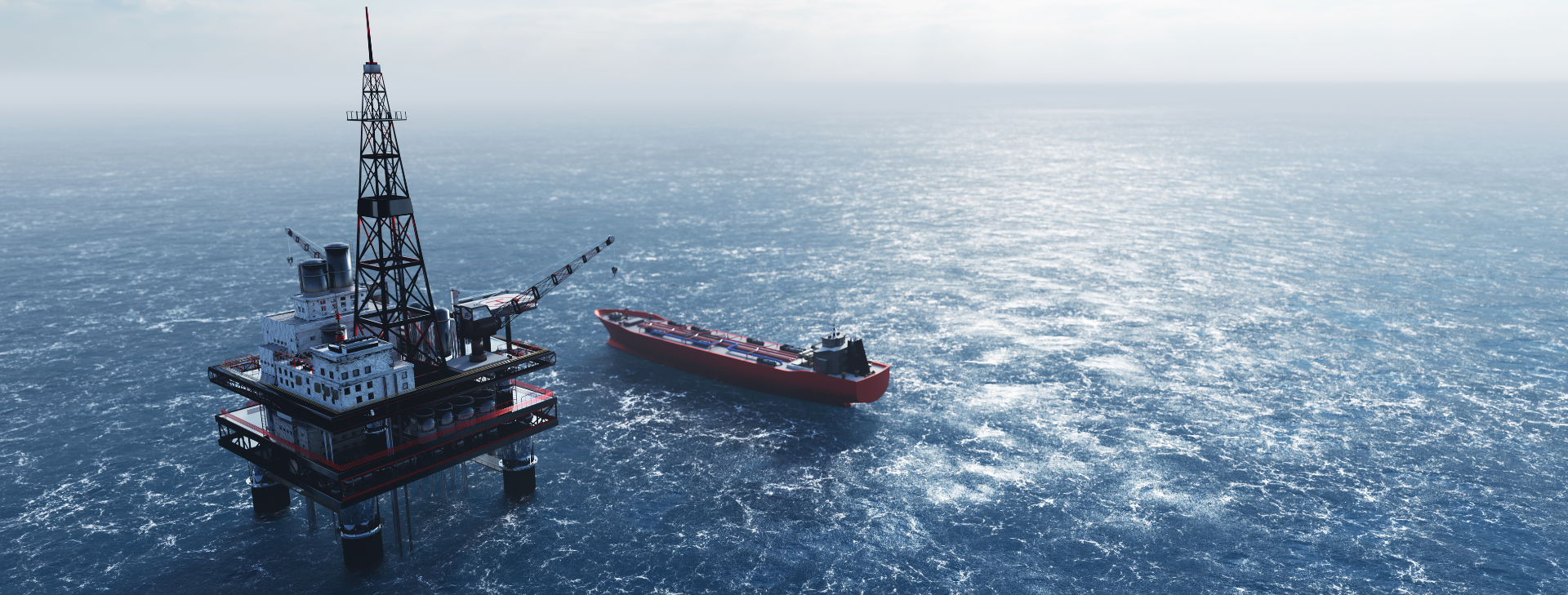

There are thousands of systems and subsystems that drive the typical offshore fixed or floating production platform and its subsea infrastructure, not forgetting the average 50 to 200 crew who operate it. Once built, all that kit needs ongoing maintenance and repair, plus some oil platforms have been operating for nearly 70 years. As technology advances or older systems become obsolete, new systems are retrofitted and old ones replaced.

So, who is responsible for installing new solutions, for maintenance and repairs, and for keeping everything not the direct responsibility of the operator working? Generally, that’s the role of the Field Service Engineer.

Viper’s Technical Team Lead Eugene Ong and Field Service Engineer Callum Maclean, both in the Product Service Delivery team, share some of their day-to-day experiences, lifting the lid on the critical role that field service engineers play in keeping oil and gas flowing – and our lights on.

What does a field service engineer actually do?

Field service engineers don’t just helicopter out to a platform, installing and servicing equipment, and fly out again.

According to Eugene, Viper Innovations’ Product Service Delivery team gets involved with every new project right from the outset: “Our involvement starts well before the first quote is sent. Our Business Development colleagues share the installation specification and schematic, asking for our input into service scope and costings.”

“We’re also the first line support for desktop diagnostics. Where a customer has a subsea installation resistance issue, they will want to know more about what is causing the resistance breakdown. If the customer has a V-LIM, a cable integrity monitor, we can complete a remote analysis.”

Other desktop support might include a customer with multiple LIM units wanting to understand if cross-talk is affecting the insulation resistance monitoring on their system. This could include reviewing field data, reviewing subsea system diagrams and compiling a report. Plus, the team completes asset condition assessments on behalf of customers.

Eugene highlights another essential role performed by the engineers in the team: “We’re the largest customer-facing part of the business. Most of the time we are interacting with operators, OEMs (original equipment manufacturers) of the subsea control system and other stakeholders during offshore operations.”

“Field Service Engineers are the face of Viper Innovations,” he adds.

Installing new V-LIMs on offshore assets

Both Callum and Eugene install V-LIMs on a wide range of OEM’s subsea control systems. Most V-LIM installations also include the activation of V-LIFE, a preventative and healing solution for low insulation resistance in umbilical cables.

“Most offshore trips initially follow a similar pattern,” says Callum. “The first day is familiarising yourself with the platform, having inductions and walkabouts, including the all-important health and safety briefing. I’ll locate the equipment that is sent out ahead of me and liaise with my point of contact. They would normally be the REP (Responsible Electrical Person) on the platform.”

“Then I check if the permit has been raised, which can sometimes take up to 48 hours, for the scope of work I complete. Very occasionally, some glitch means the permit has not been issued, so I must wait, doing what I can to help. I’ll also be checking the scope with the relevant parties. Once the kit is located, the permit is secured, and I’ve checked with the operator and other key personnel, I can get started.”

Callum will find the location on the platform where the equipment will be installed. Typically, the subsea control systems are in different locations on different platforms and press on with the install. This takes a couple of days, depending on the number of V-LIMs to be installed, and ends with thorough testing to ensure everything works as expected.

Not all installations are completed by Viper Innovations’ engineers. Sometimes, the operator or OEM may complete the task. Eugene highlights that his role includes creating detailed processes and procedures to facilitate this, as well as ensuring the Product Service Delivery team’s processes and training programmes are kept up to date.

What happens when low IR is detected?

The electrical cables in the umbilical that connect the platform with the subsea infrastructure can experience sudden drops in IR. There could be many reasons behind the IR fall, including physical damage from a storm or quality issues when the cables’ insulation was manufactured.

Whatever the cause, it is often the Viper Innovations Field Service Engineer that is sent offshore to fix it. And that trip could be to the North Sea, the Gulf of Mexico, the Eastern Mediterranean or South East Asia – anywhere in the world that a Viper Innovations solution is installed.

“When we’re called out,” says Eugene, “the operator is often highly concerned as the IR has dropped, impacting on the umbilical performance which is critical to production. They want to get it back up as quickly as possible.”

This is where the engineer’s professional skills, training, quick-thinking and calmness under pressure come into play. Callum remembers one occasion when he was out on a call and the electrical cabinets were of an unusual design and initially he couldn’t open them: “The first step was working out how to get the panel doors open safely, which I did. Then I had to dismantle the device and do fault finding. It was tense, but we got it done.”

On another occasion, the umbilical IR was so low, Callum didn’t think a recovery was possible. Like every solution, V-LIFE has operating parameters: “The chances of recovery weren’t great, and I managed the customer’s expectations accordingly. However, I went ahead, and it worked! That saved a major break in production, as the alternative was a shutdown and returning the kit to the beach for repair.”

Why work offshore as a field service engineer?

“We’re there to stop the subsea controls from going down and maintain production. When we’ve done our job, the IR has been recovered, the power stays on and production doesn’t stop, the customer is delighted,” says Callum.

Eugene has worked across the world in virtually every hydrocarbon province: “I enjoy the travel, the variety, with every day bringing a fresh challenge.”

However, there are times when you’re 300km out in the North Sea during a vicious storm with freezing horizontal rain and 10m waves crashing against the jacket, the platform alarm has gone off at 02:00, so you know it’s not a drill and you’re suiting up and racing to the muster point. That’s more challenging than the average workplace, what’s the attraction?

Callum and Eugene reply, almost simultaneously, and very simply:

“We’re keeping the lights on.”